I need to say couple of things at the outset here. The first is that I really like and admire Hugh Howey and the fact that I disagree with almost every paragraph of this post of his shouldn’t suggest that I don’t. That’s not snark or irony; it is sincere. I think it is both noble and natural for people to defend the entities and circumstances that make possible their commercial success and it is just human nature that those who have benefited from a paradigm reflexively want to defend it. I only wish that Hugh would exhibit the same respect for that tendency when it is exhibited by authors who have done well with publishers.

The other is that I don’t see the “Amazon versus the publishing establishment” battle as a moral choice, just a tug of war between competing business interests. (There are societal questions at stake, which some might see as moral choices, but the companies involved are doing what is best for them and then arguing afterwards that it is also better for society.) When I wrote what I intended to be a balanced piece about the Amazon-Hachette battle, it brought out the troops from the indie author militia in the comment string to call me to task and accuse me of many things, including being a defender of the people who pay me (although my overall revenues from Big Five publishers is actually pretty paltry with not one active consulting client among them for well over two years). I expect this post will do the same, which I find an unpleasant prospect. On the other hand, I’m sorta stubborn about saying the things I believe nobody else is saying…

I am not trying to “make a case” here for anybody: not for the publishers and obviously not for Amazon. All I am trying to accomplish is to call out what I see as the almost certainly unintended bias in the arguments as Hugh frames them. I continue to believe that self-publishing is a useful tool that most authors should employ at one time or another but that, still almost all of the time, an author who is offered a publishing deal from a major house willing to pay an aggressive advance is better off to take it than go it alone. (If you’re not offered a substantial advance, the calculus shifts, but there is a lot of work involved in self-publishing that is not described in much detail in this post, even though Hugh Howey knows much better than I do how much work it is!) And I think that generalized advice to authors to eschew publishers in a world where print still matters and stores still matter remains, as of today, unwise. That may well change in the future, but it hasn’t changed yet.

In this post, everything preceded by [HH] was written and posted by Hugh Howey. Everything preceded by [MS] is my response. I have left nothing out from Hugh’s original post.

[HH] A few weeks ago, I speculated that Hachette might be fighting Amazon for the power to price e-books where they saw fit, or what is known as Agency pricing. That speculation was confirmed this week in a slide from Hachette’s presentation to investors:

So, no more need to speculate over what this kerfuffle is about. Hachette is strong-arming Amazon and harming its authors because they want to dictate price to a retailer, something not done practically anywhere else in the goods market. It’s something US publishers don’t even do to brick and mortar booksellers. It’s just something they want to be able to do to Amazon.

[MS] Uh, yes. It is something they want to do in the market for ebooks that they don’t need to do for print. And it is something they want to do to the entity that controls 60% of their ebook sales, which no print bookseller does. And you’d be forgiven if you got the impression from this that Hachette only wanted to control the price Amazon sells at, not the price everybody sells at, keeping it the same across retailers. It does matter how you frame things…

[HH] The biggest problem with Hachette’s strategy is that Hachette knows absolutely nothing about retail pricing. That’s not their job. It’s not their area of expertise. They don’t sell enough product direct to consumers to understand what price will maximize their earnings. Amazon, B&N, Kobo, and Apple have that data, not Hachette.

[MS] But what Amazon, B&N, Kobo, and Apple know is not how to maximize Hachette’s or Hachette’s authors’ “earnings”, however they get divided between author and publisher. What they know is how to maximize their earnings and, mainly, their market share. And only Amazon and B&N have any picture of how the interaction between ebook prices and print sales works, which deeply affects an author’s and publisher’s earnings. None of the other ebook retailers have a clue about that, and Amazon doesn’t know how bookstore sales are affected (and it would be their objective to have them affected negatively, wouldn’t it?)

[HH] Beyond their ignorance of pricing strategy, Hachette also has a strong bias toward print books. Their existing relationships with major brick and mortar retailers gets in the way of their e-book pricing. This has been confirmed by my own publishers, who have admitted privately that they would like to experiment with digital pricing but don’t want to upset print book retailers. This puts their pricing strategy at odds with their investors’ needs, their authors’ needs, even their own profitability. In sum, they are making irrational decisions with their pricing philosophy. Hachette is making the same mistake that many publishers make, which is to think that harming Amazon somehow helps themselves.

[MS] Publishers are trying to keep a print book physical distribution infrastructure alive. That’s not irrational. It is rational. And it is the crux of the difference in objectives between a publisher’s strategy and Amazon’s strategy. The more bookstores fade, the better it is for Amazon and the worse it is for publishers. This is a problem you could have read about on this blog a long time ago.

[HH] The same presentation by Hachette to investors stressed the importance of DRM and the need to fight piracy. The presentation had very little to say about authors, which would be like an oil company giving a report to prospective investors and not discussing how its current wells are performing, the proven reserves it has on-hand, and what they are doing to discover new sources of oil. You know . . . the product they make their money from. Little is also said in the presentation about readers, possibly because Hachette doesn’t know who their readers are. Again, this is a presentation to investors by a company that doesn’t know its customers. Because they have too long relied on and been beholden to middleman distributors.

[MS] I’d substitute “leveraged” for “relied on and been beholden to” in the sentence that concludes that paragraph. Up until very recently, there was no efficient means or mechanism for publishers to sell directly to readers. Their “customers” were bookstores, and they understood them very well. And all the big publishers I know are investing in learning more about who are their readers. This graf begins with the complaint that authors aren’t acknowledged by publishers and ends with the complaint that publishers don’t know their readers. And the cherry on top is a biased characterization of the value and role of brick and mortar retailers. I guess the oil company reference is just to associate bad people with each other, but it otherwise seems gratuitous. The important and relevant point is that we’re still waiting for the first major author to say “no” to a publisher. It will happen, but it hasn’t happened yet.

[HH] DRM, piracy, and high e-book prices are not what a publisher should be fighting for and bragging to its investors about. Many consumers aren’t even aware that Amazon isn’t the source of their e-book DRM. Publishers (and self-published authors) opt in or opt out of DRM as they see fit. Those of us who think about the paying customer first and foremost opt out, and we are rewarded with their repeat business and their advocacy. Those of us who don’t fret over piracy invest our time where it can actually achieve something. Publishers need to adopt these same policies with all haste. More importantly, they need to stop ripping off their authors and their customers when it comes to digital pricing.

[MS] Recent data suggests pretty strongly that taking down pirate copies increases sales. But the efficacy of DRM is a good debatable point and it shouldn’t be in a paragraph that concludes with a gratuitous slam at big publisher pricing and royalties, which have nothing to do with DRM.

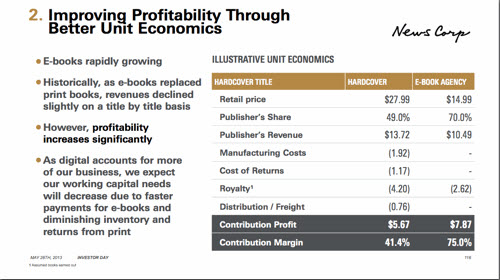

[HH] We know publishers are ripping off artists and readers when it comes to e-books. Harpercollins released this slide one year ago this month:

As author Michael Sullivan broke down in this damning blog post, it shows publishers making $7.87 on a $14.99 e-book while the author only gets $2.62. For a hardback that costs twice as much at $27.99, the publisher makes $5.67 to the author’s $4.20. What used to be a fair split is now aggressive and indefensible as publishers make more money on a cheaper product while the author makes far less. Publishers are ripping off readers and writers as they shift to digital, and they are getting away with it. They are even winning the PR campaign against Amazon, a company that has fought for lower prices for its customers and higher pay for its authors.

[MS] I agree that ebook royalties should be higher. But, in fact, only authors who sell their books to publishers without competitive bids (which indicates either “no agent” or “limited appeal generated by the proposal”) are living on that 25% royalty. The others negotiated an advance that effectively paid them far more than that. And guaranteed it before the book hit the marketplace. Publishers are making a massive PR error not raising the “standard” royalty since they effectively pay much more than that now, but the authors signing contracts with them know the truth.

[HH] Let me repeat: Publishers are waging a war here for higher prices and lower royalties. $14.99 is their ideal price for an e-book that costs nothing to print, warehouse, or ship. That’s twice what mass market paperbacks used to cost, which is what they are replacing. Reminds you of how cheaper-to-produce CDs suddenly cost twice as much as cassettes simply because they were new, doesn’t it?

[MS] Now, who’s not paying attention to authors? Right, it cost nothing to print, warehouse, or ship an ebook. But it cost something to create. And for many, if not most, publisher-published books, the publisher gave the author a substantial payment before publication. Focusing on the price without considering the value is the grossest form of “ignoring the author”. And the $14.99 price is more like the equivalent of the hardback; most publishers I know charge much less for the ebook when it is being published against a printed version that’s a paperback. And, in fact, they often charge less than $14.99 when the print edition available is a hardcover!

[HH] Publishers are also colluding with one another to offer lockstep digital e-book royalties of 25%, which is indefensible. Their every actions, when it comes to DRM, to pricing, to selling direct, to offering abusive services like Author Solutions, screams to anyone with ears that they don’t care about the writers and they don’t care about the readers. It doesn’t matter what they say, it matters what they do. And what they do is charge as much as they can get away with and take as much of the split as they possibly can. And they work with their competitors and against their retail partners to pull it off.

[MS] Publishers live in a competitive marketplace in general but nowhere more than when it comes to signing authors. The 25% hasn’t moved, but every book that is signed based on a competitive situation (one agent told me that’s at least 2/3 of them; one big publisher believes they compete for 95% of what they sign) is getting an advance that is calculated on a much higher percentage than the “standard”. So they “care” about the writers. If “caring about readers” is only demonstrated by low prices, then I’d say “Hugh has a point.” The problem is that the point is in direct conflict with “caring about the writers”, whose revenue is directly related to what readers pay (with only one exception: unearned advances paid by publishers).

[HH] Their own authors defend them, partly because they don’t spend any time investigating or understanding the business in which they are engaged. One Hachette author — a good friend of mine — said something to me the other day that made me realize they don’t understand how their books are ordered by retailers or delivered by the publisher. I suppose it’s okay to write books and not worry about the rest of the business, but this same author and friend had much to say about the Amazon/Hachette dispute, but without the basic understanding of how the relationship between those two companies works. Part of the blame for not knowing falls to publishers, who keep authors at bay and away from the business aspects of publishing. It was one of my primary complaints in that old blog post. Publishers need to embrace authors as business partners, and any author who hopes to make a career at this needs to be at least a little curious about how the industry works.

[MS] This slam at Howey’s fellow authors is both uncharacteristic of him and beneath him. The Hachette authors are doing precisely the same thing Howey is doing: defending their biggest source of revenue. What’s so surprising about that? And let’s not get too worked up about what people do and don’t understand. This piece demonstrates very little understanding of the economics of brick-and-mortar and the overall effort to sustain it as long as possible.

[HH] So we can see in their own slides that publishers do not have the best interests of their artists and consumers at heart. What about Amazon? Here we have a company that forsakes profits in order to pass along the savings to: A) Readers in the form of lower prices and to: B) Authors in the form of higher pay. That’s what we know today based on their actions. Of course, some interpret Amazon’s behavior as: “Once they are big enough, Amazon will gouge customers and take advantage of authors.” If you press on numbers, you might hear that Amazon will raise e-book prices to $12.99 one day and pay authors a miserly 25% of gross. Both of which are better than what publishers offer right now.

[MS] The pricing and split speculation is a pure straw horse. We know that what Amazon does today that pleases Howey also serves their larger strategic interests: growing market share and building the installed base of Kindle users. It’s nice when interests align. But what happens when they align tells you nothing about what will happen when they don’t. The recent changes that reduced author splits from Amazon-owned Audible shouldn’t be ignored in a paragraph like this one. (Emphasis here: I don’t think Amazon was wrong or immoral to have done this, but I think those making the argument that worrying about terms changing in the future is silly should at least acknowledge what has already happened!)

[HH] This bears repeating: The very worst that Amazon might do, in some hypothetical future, according to their fiercest critics, is still better than what publishers brag to their investors about doing today.

[MS] And this bears repeating. It’s a straw horse. The argument is attributed to these unidentified “fiercest critics” because it a straw horse. Pure speculation. Who knows what is the “the very worst that Amazon might do”?

[HH] Instead of operating under the hope that publishers will improve their business practices in the future and that Amazon will reverse course and start harming writers and readers once they gain more market share, why aren’t we condemning publishers for being the problem right now while celebrating Amazon for all they are doing to expand reading habits and to provide for artists? Why?

[MS] Simple answer. Because many authors are still being very well paid and well served by publishers. That’s why.

[HH] I think two reasons: The first is that we equate publishers to bookstores and Amazon to the loss of bookstores, and we all love bookstores. This is fallacious reasoning, though. Online shopping has impacted all of retail. These changes were inevitable, and they are the result of consumer choice. How those changes played out could have been publishers colluding with a distributor to price digital works higher than their paper counterparts. That would have been bad. Amazon leading those changes with their pricing philosophy has been good.

[MS] Much of this is true. Online shopping is inevitable; the pressure on brick-and-mortar is inevitable. And we all love bookstores, even though they don’t “map” into the future very well. But it is really disingenuous to just forget that Amazon benefits by brick stores going down faster and has discounted print books as aggressively as possible as well, which has contributed to the brick-and-mortar stores decline. I’m not demonizing Amazon over this; everybody has to run their own business and they run theirs very well. But let’s not pretend that altruism is all that is working here, or that changing circumstances couldn’t change Amazon’s pricing philosophy.

[HH] The second reason for the anti-Amazon bias is that some see Amazon as the giant and little old publishers as the underdog. That’s also wrong. The publishing and bookselling arm of Amazon is likely smaller than the combined earnings of the Big 5 publishers. Amazon makes a pittance on every e-book sold, while the Big 5 make out like bandits. Also, to say that these wings of Amazon’s operations are owned by a larger entity is to ignore that the same is true for the major publishing houses. If anything, Amazon is the clear upstart and underdog here. They are new to the market, rapidly innovating, blacklisted by brick and mortar retailers, setting up shop away from the established players, and ganged up on in an illegal manner.

[MS] No question Amazon gets “ganged up on”. We have two book businesses now: Amazon and everybody else. Everybody else includes publishers and retailers and wholesalers and agents and established authors. Amazon’s decision to “make a pittance” on certain products, including some ebooks, is tactical, not altruistic. I have to admit that characterizing Amazon as an “underdog” does activate the “gag reflex”. If this doesn’t qualify as hyperbole, I’m not sure what would. Let’s be clear and real: Amazon and Hachette are both leveraging their respective negotiating positions as best they can. It’s called business. (And,, from where I sit, it looks Amazon is in the stronger position, not Hachette. I’m not sure by what measurement Amazon could be considered the underdog here; I haven’t read any other analysis that makes that claim.)

[HH] I’ll go one step further and state something both outrageous and obvious: If the Big 5 had gotten together twenty years ago and DREAMED UP an ideal business partnership, one that would increase their distribution, provide excellent customer service to their readers, improve the livelihood of their authors, keep their backlists viable and books from going out of print, reduce their 50% return rate from bookstores to 4%, provide next-day and even same-day delivery, all while only costing them 30% instead of the 45% they lose to bookstores, they couldn’t have done better than what Amazon did for them.

[MS] Lots of truth in this paragraph, up to a point. Publishers (and authors) have benefited for years from Amazon’s willingness to sell books for almost no margin and by the shift from the less-efficient sales in stores to the more-efficient sales online. I spelled out clearly in my Amazon-Hachette post that Amazon has been the most profitable print account for most trade publishers for a long time. And I am happy to give them the full credit they deserve for making the commitment necessary to make the ebook business happen. That doesn’t change the reality that as their market share grows, we can see a concentration that changes what has been a good thing into a threat. For everybody else in the book business: those who are aware of it and those who are not.

[HH] Soak that in. Publishers should have engineered Amazon from the ground-up. A company that invests in distribution networks for their products rather than pocketing profits. And instead of celebrating all the hundreds of benefits, like pre-orders and customer reviews and the savings on print runs and returns that Amazon’s algorithms provide, they are trying to figure out how to put their best resource out of business. It boggles the mind. Like those authors who fear Amazon might take royalties away tomorrow, so are happy to give up those royalties today, publishers are siding with companies that are hurting them today out of fear of their greatest ally getting even more market share tomorrow. And readers and writers are the victims of this illogical behavior.

[MS] The unreality in the suggestion that publishers are trying to put Amazon out of business is mindboggling. I have cognitive dissonance. On the one hand, I believe Hugh Howey believes what he says. On the other hand, I can’t believe he believes that! Any publisher that thought this was possible would be deluded. The idea that it is some sort of deliberate strategy to put Amazon out of business is as far from the world we actually live in as the world of Hugh’s novels is.

[HH] What is the solution? As a writer, the solution is to retain ownership of your rights. This has never been more important than it is today. E-book royalty rates are going to move to 50% of net. I know from some insiders that this is already happening for top-name authors and hot new acquisitions. Selling your manuscript now for half of what it will be worth in the very near future is a bad move. It takes years for books to come to market with a traditional publisher. If that is your publishing goal, exercise a bit more patience. Hold on to that manuscript (or self-publish it) while you write the next. Let the market come to you.

[MS] This advice ignores the fact that a large number of authors got an advance that already pre-paid them for the royalties they could conceivably have earned by doing their own self-publishing when the publishers’ sales died. (Those “insiders” referred to are almost certainly talking about how the ebook component is calculated for advances paid to big authors, not a change in the contractual percentage.) Howey is conflating agreeing to a “half of what it should be” digital royalty with “selling your manuscript for half of what it will be worth” in the future. They’re not the same thing. I guess it’s just part of the campaign to find that first big author who turns down a publishing deal to do it themselves instead. To read this post, you’d never know we haven’t had one yet! (I thought we had one three years ago, but the one author who really threatened to do it changed his mind and signed a publishing deal with Amazon instead.)

[HH] The other option is to embrace a smaller press that has more flexibility. Online print book sales and e-book adoption have helped level the playing field for small publishers. They are becoming more viable every single day. These are the true Davids. They now have the tools and ability to see their works sell to a wide audience and win awards. I put them as the second best option behind self-publishing, and I include Amazon’s imprints in this category. They offer higher royalty rates and terms similar to small presses, though some have grumbled lately that Amazon’s imprints are becoming more and more like the Big 5, so watch what you sign.

[MS] I’m always happy to see smaller presses succeed, but they have a hard time competing against the Big Five, mainly because of Amazon. They are forced (by Amazon) to sell their ebooks on “wholesale” terms, which means giving much more of the retail price they set to the supply chain. This leaves them two choices. They can set a reasonable retail price (like an Agency price) and get nearly 30% less revenue than an Agency publisher. Or they can set an artificially high price and hope the retailer will discount from it. So even if they give the author a higher percentage of ebook sales, the net might not be higher. It is hard to succeed in today’s environment as a small press, not easy.

[HH] For readers, keep doing what you’re doing. Self-publishing and small presses are booming because you care about great stories, not where they come from. You are the disruptive force in this industry, and I say that with every ounce of love I can muster. Keep disrupting by doing what you do best: Read. Write reviews. Share your enthusiasm. Infect others. Spread the joy of this greatest of pastimes. And we will trust that those who cater to your needs and to the needs of the artists you admire will be the ones who come out on top. All others will need to change their ways or perish. If they do the former, let’s cheer for them. If they persist in the latter, let’s not be sad to see them go.

[MS] I am not happy to see anybody go. The desire to make villains out of the industry establishment is the most unattractive trait of what should be a hero class: intrepid authors who forge ahead without institutional support to make success happen. There is no doubt that Amazon has made that opportunity possible for most of them and it is easy to understand why anybody who has profited from the infrastructure Amazon created would celebrate it and want to see it grow. But author success has been achieved in a wide variety of ways and the way Hugh Howey has done it is still very much the exception, not the rule. We shouldn’t leap to conclusions from unusual cases. And I think it is an iron rule of nature that it is dangerous to generalize from one’s own personal experience.

I see from a subsequent post of Hugh’s that he will be in Toronto this week at Book Summit, as will I. I hope we’ll have a chance to have a Diet Coke and talk about this while we’re up there. My Logical Marketing Agency partner Pete McCarthy and I are kicking off the show on Tuesday morning. I always love visiting Toronto.